How to stop catastrophizing

Nothing in life is to be feared. It is only to be understood.

Marie Curie

Putting things in perspective is one way to tame fear.

Constant fearmongering from the media worldwide created unprecedent coronaphobia in the world population. The negative potentials of this powerful phobia must not be minimized. We are already witnessing worrisome trends and actions (lack of compassion, harshness, justification of liberticide measures, violence promoting speeches.) Therefore, it is imperative to readjust this phobia and to put upfront the worldwide reality of this pandemic. It is imperative to stop catastrophizing. This can be achieved by understanding the virus and its real impact around the world.

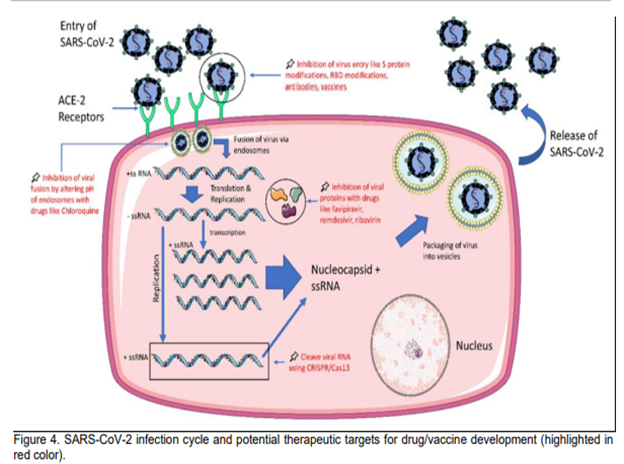

The mechanism of action of the SARS-Cov-2 virus is well known.

The victimology of the virus is also well known; it hits mostly the vulnerable individuals and system. As seen before in lesson 1, the crisis served to highlight their fragility in terms of health, and socio-economy, hitting the most deprived; of nourishment, finance or resources. Therefore, one way to control the infection would be to solidify these fragile and vulnerable elements.

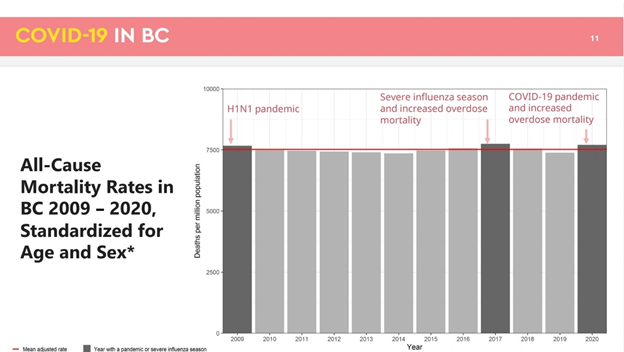

Virus being virus and human being human being, a real deadly virus. such as SARS-CoV-2 virus is portrayed to be, would be deadly in all parts of the world regardless of the political, societal or medical response. We have been witnessing, pain, death, suffering, distress. Are those impacts of a deadly virus or manifestations of societal lack, inadequate crisis response and political management of health? Looking at different parts of the world, unbiased statistics analysis and knowledge review will help you answer this question.

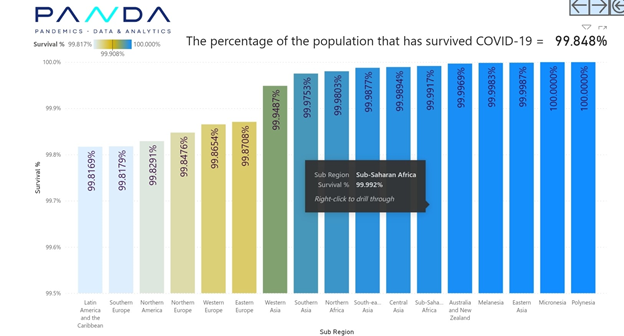

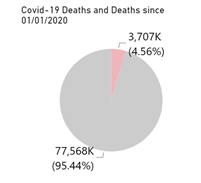

SURVIVAL RATE

CUBAN RESPONSE

Original article

Wylie, L.L. (2021), “Cuba’s response to COVID-19: lessons for the future”, Journal of Tourism Futures, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-10-2020-0187

Cuba’s response to COVID-19: internal measures

COVID-19 first arrived in Cuba in March 2020 with three Italian tourists. They were diagnosed on March 11, the country was in “lockdown” mode by March 20, and by March 24, Cuba had closed its borders.

Cuba’s lockdown entailed the closure of schools and businesses, mandating masks and the isolation of COVID-19 positive patients, among others. Most significantly for the economy, Cuba closed the border which brought an abrupt halt to tourism, one of the country’s primary sources of foreign exchange.

Case numbers and comparisons

While differences in testing protocols, case counting and death reporting make comparisons difficult, it appears that Cuba managed the pandemic better than most of the other states in the Caribbean and much better than many wealthier states. By January 10, 2021, Cuba had a total of 14,576 cases and 151 cumulative deaths (13 deaths per 1 million people) (Worldometers, 2021). Compare that to Jamaica with 312 deaths (105 deaths per 1 million people) or the Dominican Republic with 2,427 deaths (223 deaths per 1 million people). By this same date, the USA had reached 1,151 deaths per 1 million people (Worldometers, 2021). By most measures, Cuba has performed extraordinarily well during one of the most challenging periods in its history. The primary credit for this success has been given to Cuba’s unique community-based medical system.

Secrets of success: community-based medicine and biomedical research

Cuba’s health indicators are impressive both when compared to other states with similar Gross National Products and when set beside much wealthier countries including the USA. For example, Cuban life expectancy at birth (2018) is 79 years, which exceeds other states in the region, such as the Dominican Republic and the Bahamas where it is 74 years (World Bank, 2020a). Moreover, life expectancy in Cuba is the same as life expectancy in the USA. The recent figures for infant mortality are similarly impressive (4 per 1,000 live births); the same as the UK and Canada and better than the American figure of 6 per 1,000 (World Bank, 2020b).

Cuba has free universal health care and prioritizes access to medical personnel and preventive medicine. At 84 doctors for every 10,000 individuals, Cuba has the highest ratio of doctor-to-citizen in the world. By this measure there is a substantial difference between Cuba and the USA, which has a mere 26 doctors per 10,000 people (WHO, 2020).

It is not just the number of medical personnel but also the unique way they deliver their services that have contributed to Cuba’s impressive statistics. The heart of the Cuban health-care system is the local neighborhood of approximately 1,000 individuals. Resident in each neighborhood is a family physician and nurse who provide care to the local population and emphasize preventive health education.

Community based medicine: the pandemic response

This ease of access of the Cuba population to medical staff, information and treatment was a significant factor in Cuba’s ability to manage the pandemic. The well-honed neighborhood medical system that rapidly implemented a systematic door-to-door medical survey allowed the Cuban state to quickly identify and isolate cases. This system, known as Continuous Assessment and Risk Evaluation (CARE) is integral to the Cuban model as medical teams regularly go house-to-house to discuss everything from diet to disease treatment with their patients (Gorry, 2020). Furthermore, symptom canvasing also occurs during dengue or other outbreaks.

The canvassers received additional training on identifying COVID-19 symptoms in January, two months prior to the arrival of the virus on the island (Aguilar-Guerra and Reed, 2020; Gorry, 2020) Thus, soon after the first cases had been reported, the entire population of the country had discussed COVID-19 with a medical expert. This system has facilitated efficient contact tracing, isolation and testing.

Cuba’s model, already widely acknowledged as innovative, is being accorded accolades for its pandemic response. An article in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine declared, “With a health system grounded in public health and primary care, the country invests heavily in producing health workers who are primarily trained to work in the community, […] Their efforts with COVID-19 have been outstanding” (Ashton, 2020). Likewise, an article in Medicc Review asserted “the backbone of Cuba’s universal public health system is also the backbone of its response to the Coronavirus pandemic” (Aguilar-Guerra and Reed, 2020). Public health officials in other countries should take note of Cuba’s CARE model and its success, not only in containing the spread of COVID-19 but also of the positive effects of preventative health measures and community medicine on the overall health of the population. In the spring of 2020, Cuba received the highest evaluation for its pandemic response from the Oxford Stringency Index (Hale et al., 2020; Oxford, 2021).

Biomedical research

The health-care system also benefits from Cuba’s exceptional investment in biomedical research and planning. In January 2020, Cuba began to organize its virus response plan, formulating solutions for possible scenarios and expanding laboratory capabilities (Ashton, 2020; Pérez, 2020).

Cuba is perhaps best known for its innovative research on vaccines, including a vaccine that treats lung cancer, but it has also developed medicines in many other categories. This experience was harnessed during the COVID-19 outbreak when seven of Cuba’s biomedical research facilities transitioned to focus on COVID-19 vaccines and treatments.

Although it remains too early to state definitively, a Cuban drug, Interferon alfa-2b, has shown potential as a treatment for COVID-19, as have drugs Jusvinza (CIGB 258) and Itolizumab (Dasgupta, 2020; Horta, 2020; Pereda et al., 2020). In addition, given Cuba’s strength in vaccine research, it is not surprising that the first Latin American vaccine for COVID-19 approved for clinical trials was developed in Cuba (Cardonne, 2020). In early 2021, Cuban vaccine candidates Soberana 2, Mambisa (CIGB-669) and Abdala (CIGB-66) looked promising (Santos and Bandomo, 2020).

Cuba’s international response: medical diplomacy

Cuba has a long history of medical diplomacy, reaching back to the 1960s when the country sent a team of medical workers to Algeria during its war of independence. Since then, Cuba has frequently responded to international disasters with its medical personnel, treating patients in the Caribbean after hurricanes or in Africa during the height of the HIV/AIDs crisis. Since 2005, the process has been coordinated through Cuba’s rapid response medical team, the Henry Reeve International Medical Brigade. Consisting of over 7,000 medical personnel, it is designed to quickly respond to crises around the world, aiding populations in dozens of countries undergoing natural disasters or epidemics.

These missions are widely admired. In fact, President Obama was impressed by Cuba’s efforts and noted that when Latin American leaders “spoke about Cuba they talked very specifically about the thousands of doctors from Cuba that are dispersed throughout the region, and upon which many of these countries heavily depend” (Wylie, 2012). Former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon called Cuban doctors “miracle workers” (Ban, 2014). In 2017, Cuba received the WHO Public Health Prize in recognition of these international endeavors.

Cuba’s global response to the pandemic has been extraordinary. Cuba sent its medical teams to Wuhan in January 2020 and shortly thereafter a team went to Italy where they built and then treated COVID-19 patients in a field hospital in Lombardy (Ashton; Doctors, 2020). During the pandemic, Cuban teams helped in dozens of countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Europe and the Middle East (Cuba Minrex, 2020).

Likewise, Cuba accepted the British cruise ship MS Braemar that was turned away by other countries because it had COVID-19–infected passengers onboard, prompting praise by the British ambassador to Cuba and the British foreign secretary (Stone, 2020).

Recognition is widespread. The head of CARICOM, Ralph Gonsalves, explained, “They are lifesavers, […] In some Caribbean countries, they constitute the backbone of the response to the pandemic” (NBC News, 2020). In the summer of 2020, over 30,000 people campaigned to nominate these Cuban medical teams for a Nobel Peace Prize. One of these people, Noam Chomsky declared that Cuba was the “only country to have shown genuine internationalism during coronavirus crisis” (Donmez, 2020).

Vulnerabilities impeding Cuba’s response to the pandemic

Despite its success, Cuba’s ability to respond as effectively as possible to the pandemic has been hampered by the ongoing economic crisis principally brought on by six decades of American hostility. President Trump’s tightening of the American embargo reversed many of the changes initiated by President Obama, which further damaged the Cuban economy just in time for the pandemic. Trump also targeted Cuba’s medical internationalism during the outbreak by pressuring receiving states to refuse Cuba’s offer of medical aid (The Guardian, 2020). While all of Cuba’s economic woes cannot be blamed on American hostility, it is the most obvious single challenge to the Cuban economy, worsening poverty and hampering Cuba’s ability to weather the pandemic.

Cuba’s relative poverty creates three main stumbling blocks in a pandemic. First, Cuba suffers from a severe housing shortage, which leads to overcrowding and complicates the population’s efforts to social distance (Borkowicz et al., 2017). Second, because Cuba is dependent on other countries for most of its food, the pandemic has worsened food insecurity (Marsh, 2020). Third, the poor condition of some basic infrastructure such as roads and communication networks hampers the state’s otherwise effective response to crises. In particular, the relatively underdeveloped internet and e-commerce systems on the island have impaired Cuban citizens’ ability to purchase necessities online and thus reduce community contact. However, the pandemic has brought attention to these problems, spurring change, including the development of an e-commerce platform devoted to the hospitality sector (Carrero, 2020).

Return to tourism

Cuba’s relatively successful management of the pandemic has allowed the country to welcome tourists again. The government began with a phased reopening on June 1, allowing the resumption of domestic tourism, followed by a partial reopening of international travel to isolated keys adjacent to the mainland on July 1. Access to the keys are restricted, thus limiting contact between Cubans and visitors. Cuba’s most popular resort area, Varadero, reopened on October 15, along with many other areas of the country, excluding Havana. The government’s phased opening was meant to control and monitor the return to tourism.

Cuba has made many changes to protect tourists and Cubans they encounter through the “Turismo + Higienico y Seguro” (more hygienic and safe) program, which regulates and monitors tourist facilities for disease prevention protocols (Kucheran, 2020). Furthermore, tourist hotels are now staffed with a doctor, nurse and epidemiologist (Harris, 2020). Thus, Cuba’s first planeload of tourists arrived in Cayo Coco on September 4, reflecting confidence in Cuba’s management of the pandemic. The government has continued to update protocols since, instituting airport testing and as of January 10, 2021, mandating a prearrival polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for most visitors (Frank, 2021).

Cuba, Ministry of Tourism of Cuba (2020) is using Cuba’s new protocols and low numbers to promote Cuban tourism in a new advertising campaign called “Breathe” and with the #CubaYourSafestDestination (see www.facebook.com/MinturCuba.ca/videos/1564261290419773). As Cuban economist, Ricardo Torres explained, “Cuba’s very successful strategy in controlling the epidemic is also an asset when it comes to opening up, […] because the tourists in the coming months will be looking for safe destinations from a health perspective” (Cuba Reopens CGTN [2020]). This approach also builds on Cuba’s reputation as a health tourism destination. In addition to vaccinating its population and donating its vaccines to poorer countries, “Cuba is floating the idea of enticing tourists to its shores with the irresistible cocktail of sun, sand and a shot of Sovereign 2 [Sobreana 2].” (Augustin and Kitroeff, 2021) Although this strategy shows promise, it is too early to measure the success of the new campaign and further analysis of the impact of the return of tourism on the spread of the disease will also need to be conducted.

Lesson learned: in Cuba and globally

The Cuban state acknowledges that it could learn from its response to the pandemic. In particular, the state said the pandemic helped it to identify how the country could improve its readiness for future crises, including strengthening Cuba’s e-commerce and home delivery services and increasing domestic production of essential goods.

More importantly, there are significant lessons for other countries from Cuba’s pandemic response. The Cuban example shows the benefits of a robust but low-cost community-based medicine program and the benefits of working globally to combat outbreaks through the sharing of medical staff and resources. Cuba’s medical diplomacy demonstrates that a state’s response during crisis can moderate the global inequities and injustices such as unequal access to care that often accompany disease outbreaks such as COVID-19.

References

Aguilar-Guerra, T.L. and Reed, G. (2020), “Mobilizing primary health care: Cuba’s powerful weapon against COVID-19”, MEDICC Review, Vol. 22 No. 2, p. 54.

Ashton, J. (2020), “Shoe leather epidemiology in the age of COVID: lessons from Cuba”, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, Vol. 113 No. 7, pp. 282-283.

Augustin, E. and Kitroeff, N. (2021), “Coronavirus vaccine nears final tests in cuba”, Tourists May Be Inoculated, New York Times, 17 February, available at www.nytimes.com/2021/02/17/world/americas/coronavirus-cuba-vaccine.html (accessed 22 February 2021).

Ban, K. (2014), “Secretary-General hails Cuba for training medical ‘miracle workers’, being on frontlines of global health”, The UN website, available at www.un.org/press/en/2014/sgsm15619.doc.htm (accessed 15 Octobe 2020).

Borkowicz, I., Scheerlinck, K. and Schoonjans, Y. (2017), “A symbiotic relation of cooperative social housing and dispersed tourism: a new urban regeneration model for Havana, Cuba”, Journal of Research in Architecture and Planning, Vol. 23, pp. 31-40.

Cardonne, T.M., Semanat, D.Y.G., Llago, S.L. and Reyes, E.J.M. (2020), “Investigaciones clínicas sobre COVID-19. Una breve panorámica. Anales de la Academia de Ciencias de Cuba”, Annals of the Cuban Academy of Sciences, Vol. 10 No. 3, p. 910.

Carrero, Y. (2020), “Feature: Cuba develops first e-commerce platform to promote post-pandemic tourism”, Xinhua, available at: www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-09/18/c_139378191.htm (accessed 13 October 2020).

CGTN (2020), “Cuba reopens after 8-month shutdown but faces challenge wooing back tourists”, CGTN November 21, 2020, available at: https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-11-21/Cuba-reopens-but-faces-challenge-wooing-back-tourists-VBb2VdBqyk/index.html (accessed 12 January 2021).

Cuba Minrex (2020), “Infographic map update. 22 ‘henry reeve’ medical brigades in 21 nations to face the new COVID-19 pandemic”, available at: www.minrex.gob.cu/en/infographic-map-update-22-henry-reeve-medical-brigades-21-nations-face-new-COVID-19-pandemic (accessed 28 October 2020).

Cuba, Ministry of Tourism of Cuba (2020), “#ProtocoloTurismoCubano #CubaYourSafestDestination”, available at: www.facebook.com/MinturCuba.ca/videos/1564261290419773 (accessed 10 January 2021).

Dasgupta, A. (2020), “Seeking an early COVID-19 drug, researchers look to interferons”, The Scientist, July 20, available at: www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/seeking-an-early-COVID-19-drug-researchers-look-to-interferons-67753 (accessed 23 October 2020).

Donmez, B.B. (2020), “30,000 back US campaign seeking nobel for cuban doctors”, Anadolu Agency 27 July, available at: www.aa.com.tr/en/culture/30-000-back-us-campaign-seeking-nobel-for-cuban-doctors/1924106 (accessed 10 January 2021).

Duffy, L. and Kline, C. (2018), “Complexities of tourism planning and development in Cuba”, Tourism Planning & Development, Vol. 15 No. 3, pp. 211-215, doi: 10.1080/21568316.2018.1440830.

Elliott, S.M. and Neirotti, L.D. (2008), “Challenges of tourism in a dynamic island destination: the case of Cuba”, Tourism Geographies, Vol. 10 No. 3, pp. 375-402, doi: 10.1080/14616680802236386.

Firmat, G. (2010), “Introduction: so near and yet so foreign”, The Havana Habit, Yale University Press, New Haven, pp. 1-22, available at: www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1nqb6j.4 (accessed 11 January 2021)

Frank, M. (2021), “Tourists trickle back to Havana despite tough COVID-19 protocols”, Reuters January 7, 2021, available at: www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-cuba-tourism-idINKBN29C226?edition-redirect=in (accessed 10 January 2021).

Gorry, C. (2020), “COVID-19 case detection: Cuba’s active screening approach”, MEDICC Review, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 58-63.

Hale, T., Sam, W., Anna, P., Toby, P. and Beatriz, K. (2020), Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government, Oxford University.

Harris, W. (2020), “Where can Canadians travel right now? Mexico, Jamaica and Cuba top the list”, The Globe and Mail, 20 October, available at: www.theglobeandmail.com/life/travel/article-is-going-south-an-option-this-winter (accessed 24 October 2020).

Horta, M.D.C.D. Sr., (2020), “CIGB-258 immunomodulatory peptide: a novel promising treatment for critical and severe COVID-19 patients”, medRxiv, available at: www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.05.27.20110601v1.full.pdf+html (accessed 22 October 2020).

Kucheran, K. (2020), “Cuba reopening for tourism- everything you need to know”, Travel off Path, 22 October, available at: www.traveloffpath.com/cuba-reopening-for-tourism-everything-you-need-to-know/ (accessed 22 October 2020).

Marsh, S. (2020), “Facing crisis, Cuba calls on citizens to grow more of their own food”, Reuters, June 29, available at: https://ca.reuters.com/article/idCAKBN2402P1 (accessed 24 October 2020).

NBC News (2020), “Cuba sends ‘white coat army’ of doctors to fight coronavirus in different countries”, available at: www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/cuba-sends-white-coat-army-doctors-fight-coronavirus-different-countries-n1240028 (accessed 15 October 2020).

Pereda, R., González, D., Rivero, H., Rivero, J., Pérez, A., López, L., Mezquia, N., Venegas, R., Betancourt, J. and Domínguez, R. (2020), “Therapeutic effectiveness of interferon-α2b against COVID-19: the Cuban experience”, Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research, Vol. 40 No. 9, doi: 10.1089/jir.2020.0124.

Pérez, R.A. (2020), “The Cuban strategy for combating COVID-19”, MEDICC Review, Vol. 22 No. 3, pp. 64-68.

Santos, I.C. and Bandomo, G.A.V. (2020), “Rapid response: candidate vaccines in Cuba”, BMJ, p. 371, doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4654.

Stone, J. (2020), “UK thanks Cuba for ‘great gesture of solidarity’ in rescuing passengers from coronavirus cruise ship”, Independent, 07 April, available at: www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/coronavirus-cruise-ship-cuba-rescue-ms-braemar-havana-cases-a9451741.html (accessed 24 October 2020).

The Guardian (2020), “Trump puts Cuban doctors in firing line as heat turned up on island economy”, available at: www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/feb/11/trump-puts-cuban-doctors-in-firing-line-as-heat-turned-up-on-island-economy (accessed 25 October 2020).

Trading Economics (2021), “Cuba tourist arrivals: 2008-2020 data”, available at: https://tradingeconomics.com/cuba/tourist-arrivals (accessed 11 January 2021).

World Bank (2020a), “Life expectancy at birth”, available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.INWorld (accessed 16 October 2020).

World Bank (2020b), “Mortality rate infant”, available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.IMRT.IN?most_recent_value_desc=false (accessed 16 October 2020).

World Health Organization (2020), “Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard”, available at: https://COVID19.who.int/table (accessed 16 October 2020).

World Health Organization (2020), “Medical doctors”, available at: www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/medical-doctors-(per-10-000-population (accessed 16 October 2020).

Worldometers (2021), “Coronavirus”, available at: www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#countries (accessed 10 January 2021).

Wylie, L. (2012), “The special case of Cuba”, International Journal: Canada’s Journal of Global Policy Analysis, Vol. 67 No. 3, pp. 661-684, available at: www.jstor.org/stable/42704919 (accessed 12 January 2021).

Further reading

CBC News (2020), “Halifax travel agency pitches plan to expand Atlantic bubble to Cuban resort”, available at: www.cbc.ca/news/business/atlantic-bubble-cuba-1.5778806 (accessed 28 October 2020).

Galbán-García, E. and Pedro, M.-B. (2020), “COVID-19 in Cuba: assessing the national response”, MEDICC Review, Vol. 22 No. 4.

Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (2021), available at: www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker (accessed 11 January 2021).

Rodriguez, A. (2020), “Cuba relaxes coronavirus restrictions seven months into pandemic”, CTV News, 12 October, available at: www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/cuba-relaxes-coronavirus-restrictions-seven-months-into-pandemic-1.5142276 (accessed 21 October 2020).

Telesur (2020a), “Doctors who fought COVID-19 in Italy returned to Cuba”, available at: www.telesurenglish.net/news/doctors-who-fought-COVID-19-in-italy-returned-to-cuba-20200721-0007.html (accessed 18 October 2020).

Telesur (2020b), “Near a million Cubans use e-commerce as improvements continue”, available at: www.telesurenglish.net/news/Near-a-Million-Cubans-Use-E-Commerce-As-Improvements-Continue-20200821-0016.html (accessed 24 October 2020).

The Caribbean Council (2020), “Cuba to begin phased recovery from impact of COVID-19”, available at: www.caribbean-council.org/cuba-to-begin-phased-recovery-from-impact-of-COVID-19/ (accessed 26 October 2020).

Xinhua (2020), “Cuban president urges to solve housing shortage”, available at: www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-09/24/c_137488943.htm (accessed 18 October 2020).

Yaffe, H. (2020), “The world rediscovers Cuban medical internationalism”, LSE: Latin America and Caribbean Centre, 8 April, available at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/latamcaribbean/2020/04/08/the-world-rediscovers-cuban-medical-internationalism/ (accessed 10 January 2021).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dana Shuqom for her research assistance and Tazim Jamal for her support and encouragement. The author would also like to thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council for their support. The research contained in this publication is supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Corresponding author

Lana L. Wylie can be contacted at: wyliel@mcmaster.ca

About the author

Lana L. Wylie is based at the Department of Political Science, Faculty of Social Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada. She research focuses on Canadian and American foreign policy, Latin American and Caribbean politics with an emphasis on Cuba and international relations. She is the recipient of a research grants or fellowships from the Canadian International Council and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada to study the Canadian–Cuban relationship. She was the guest editor of an issue of Canadian Foreign Policy Journal entitled “The Politics of Canada-Cuba Relations: Emerging Possibilities and Diverse Challenges.” Her book, Perceptions of Cuba: Canadian and American Polices in Comparative Perspective (University of Toronto Press, 2010) compares Canadian and American policies toward Cuba. She has three co-edited volumes on Canadian foreign policy or policy toward Cuba. They are Canadian Foreign Policy in Critical Perspective (with J. Marshall Beier) (Oxford University Press, 2010); Our Place in the Sun: Canada and Cuba in the Castro Era (with Robert Wright) (University of Toronto Press, 2009); and Other Diplomacies, Other Ties: Cuba and Canada in the Shadow of the US (with Luis René Fernández Tabío and Cynthia Wright) (University of Toronto Press, 2018). This last co-edited volume conceptualizes the Cuba–Canada relationship through interactions among non-state actors across cultural, state, linguistic and similar boundaries. Her most recent research focuses on the connections between tourism and diplomacy.

Related articles

- COVID-19 to end Cuban economic reformExpert Briefings, 2020

- The impact of COVID-19 global health crisis on stock markets and understanding the cross-country effectsEda Orhun, Pacific Accounting Review, 2021

- Traditional Chinese medicine as a tourism recovery drawcard to boost China’s inbound tourism after COVID-19Jun Wen et al., Asia Pac Journal of Mark and Log, 2021

- The Anticipated Future of Public Health Services Post COVID-19: ViewpointHaitham Bashier Mohannad Al Nsour Yousef Khader Mumtaz Khan Magid Al Gunaid, JMIR Public Health Surveill

- Global impacts of pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic: Focus on socio-economic consequencesNT Pramathesh Mishra et al., Sensors International, 2020

- COVID-19 in New York City as an Extreme Event: The Disruption and Resumption of the Global CitySteven Cohen, World Scientific, 2021

© 2021 Emerald Publishing Limited

About

- About EmeraldOpens in new window

- Working for EmeraldOpens in new window

- Contact usOpens in new window

- Publication sitemap

Policies and information

- Privacy notice

- Site policies

- Modern Slavery ActOpens in new window

- Chair of Trustees governance statementOpens in new window

- COVID-19 policyOpens in new window

- Accessibility

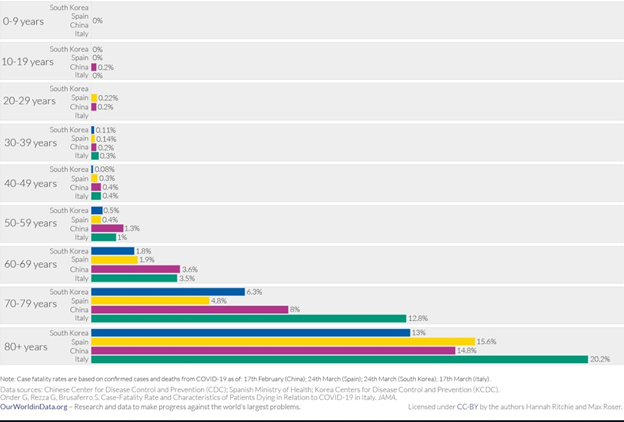

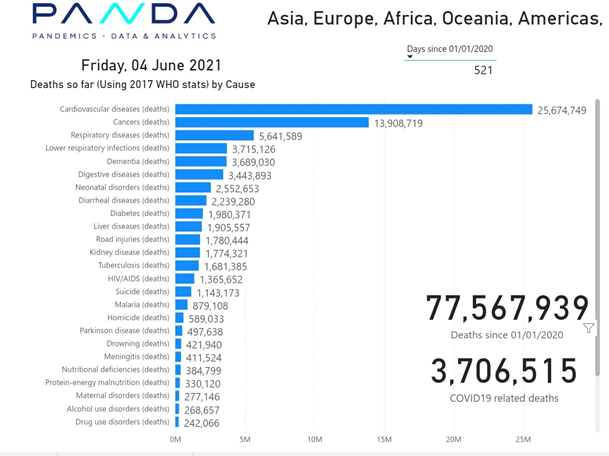

FATALITY AND DEATH

According to PANDA Data, SARS-CoV-2 viral infection is responsible for 4,56 % of global death. At the time of the writing this lesson, WHO data regarding 2020 global death was not available, therefore lets compare the 4.56% calculated by PANDA to the 2019 WHO data for the top 10 causes of death.

The top 10 causes of death (WHO)

9 December 2020العربية中文FrançaisРусскийEspañol

In 2019, the top 10 causes of death accounted for 55% of the 55.4 million deaths worldwide.

The top global causes of death, in order of total number of lives lost, are associated with three broad topics: cardiovascular (ischaemic heart disease, stroke), respiratory (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lower respiratory infections) and neonatal conditions – which include birth asphyxia and birth trauma, neonatal sepsis and infections, and preterm birth complications.

Causes of death can be grouped into three categories: communicable (infectious and parasitic diseases and maternal, perinatal and nutritional conditions), noncommunicable (chronic) and injuries.

Leading causes of death globally

At a global level, 7 of the 10 leading causes of deaths in 2019 were noncommunicable diseases. These seven causes accounted for 44% of all deaths or 80% of the top 10. However, all noncommunicable diseases together accounted for 74% of deaths globally in 2019.

The world’s biggest killer is ischaemic heart disease, responsible for 16% of the world’s total deaths. Since 2000, the largest increase in deaths has been for this disease, rising by more than 2 million to 8.9 million deaths in 2019. Stroke and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are the 2nd and 3rd leading causes of death, responsible for approximately 11% and 6% of total deaths respectively.

Lower respiratory infections remained the world’s most deadly communicable disease, ranked as the 4th leading cause of death. However, the number of deaths has gone down substantially: in 2019 it claimed 2.6 million lives, 460 000 fewer than in 2000.

Neonatal conditions are ranked 5th. However, deaths from neonatal conditions are one of the categories for which the global decrease in deaths in absolute numbers over the past two decades has been the greatest: these conditions killed 2 million newborns and young children in 2019, 1.2 million fewer than in 2000.

Deaths from noncommunicable diseases are on the rise. Trachea, bronchus and lung cancers deaths have risen from 1.2 million to 1.8 million and are now ranked 6th among leading causes of death.

In 2019, Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia ranked as the 7th leading cause of death. Women are disproportionately affected. Globally, 65% of deaths from Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia are women.

One of the largest declines in the number of deaths is from diarrhoeal diseases, with global deaths falling from 2.6 million in 2000 to 1.5 million in 2019.

Diabetes has entered the top 10 causes of death, following a significant percentage increase of 70% since 2000. Diabetes is also responsible for the largest rise in male deaths among the top 10, with an 80% increase since 2000.

Other diseases which were among the top 10 causes of death in 2000 are no longer on the list. HIV/AIDS is one of them. Deaths from HIV/AIDS have fallen by 51% during the last 20 years, moving from the world’s 8th leading cause of death in 2000 to the 19th in 2019.

Kidney diseases have risen from the world’s 13th leading cause of death to the 10th. Mortality has increased from 813 000 in 2000 to 1.3 million in 2019.

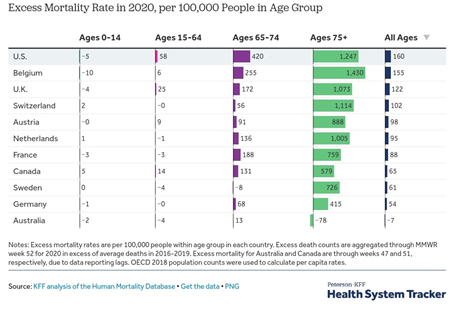

Only in the US, can we see an excess death rate for 2020 compared to the 2016-2019 period, amongst the young demographic.

THE WORLD IN DATA

EL SALVADORE

Not every country rely on vaccine as unique means of controlling the crisis. Salvadoran government adopted measures in alignment with the recommendation of the Front Line Critical Care Alliance in regards to early treatment with Ivermectin as key component.

HAITI’S SARS-CoV-2 MYSTERY

Despite lax rules, COVID-19 claims few lives in Haiti. Scientists want to know why.

by Jacqueline Charles

In Haiti, they are acting like COVID-19 doesn’t exist.

Mask-wearing is an exception and not the norm; bands are playing to sold-out crowds; and Kanaval, the three-day pre-Lenten debauchery-encouraging street party is back on for February.

This is not a case of a population simply in denial. In a country of roughly 11 million people, there have been an astoundingly low 234 confirmed deaths related to the novel coronavirus. Across the border in the neighboring Dominican Republic, with roughly the same population, the pandemic has killed almost ten times the number, 2,364. Jet off to Miami-Dade County, home to one of the larger Haitian communities in the United States, and the death toll is even higher: 4,002 in a population of 2.7 million.

What’s going on? Nobody is sure.

“We don’t have a large quantity of people who are in bad shape,” said Dr. Sophia Cherestal Wooley, deputy medical coordinator for Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières in Port-au-Prince. “They don’t get sick to the point that they need to be hospitalized and we don’t have the same quantity of people who have died here like in the Dominican Republic.

“Sincerely, I don’t have an explanation as to why,” she said. “We cannot say that the virus isn’t in circulation and I don’t think Haiti has a different virus that’s circulating. It’s the same as the others because there have been no studies saying otherwise.”

Shortly after the first imported case of COVID-19 was confirmed in Haiti on March 19, epidemiologists raised alarms. Taking into account Haiti’s weak health system, crowded living conditions and the population’s skepticism about the virus, they feared that the country, which has seen so much tragedy, would be overwhelmed by COVID-19 infections.

At best, there would be 2,000 deaths, the models predicted. At worst, around 20,000.

Even the Pan American Health Organization, citing a surge of Haitians crossing the border from the Dominican Republic to escape a spike there and the country’s ongoing political and humanitarian crises, voiced concerns about a pending crisis.

But fears that the deadly pandemic could unleash civil unrest and an even deeper humanitarian crisis have so far not proven accurate.

“Today Haiti has been mildly affected compared to other countries in the region,” Dr. Sylvain Aldighieri, incident manager at the Pan American Health Organization, said. “But the collateral effects, the socioeconomics, health and nutritional are considerable.”

Still, the low number of deaths is especially surprising because of the government’s own chaotic response and lax enforcement of its own rules.

Ministry of Health surveillance data show that Haiti experienced a first peak at the end of May into early June, and hospitalizations, while rising at one point, never reached critical levels.

In late August, a month before the U.S. government handed over 37 ventilators to the country to respond to COVID-19, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières closed its COVID-19 treatment center after only three months of operation. In recent months, other units have also closed, and plans to turn local soccer stadiums into oversized hospitals, never materialized.

Though public health experts are relieved about the death toll, they also warn that other health indicators suggest the country is not out of the woods.

“What we have to remember is that we are confronting a deadly disease, a new virus that probably has not yet manifested itself fully,” said Dr. Jean Hughes Henrys, a member of the government-backed scientific commission supporting the COVID-19 response. “We have to remain vigilant.”

On Monday, Haiti reported a total of 9,588 confirmed cases since March. In comparison, the Dominican Republic has registered 155,000 infections.

This week, health workers on the front lines of the pandemic were warned that the country may be heading into a second wave. Not only is the country experiencing an uptick in laboratory confirmed cases, but the positivity rate has gone from almost 9 percent in November to almost 16 percent last week. The majority of the cases are coming mostly from the United States, particularly Florida, and the Dominican Republic.

“Does that mean people should be panicked? I don’t believe panicking solves anything,” said Henrys, who is also director of laboratory research at Port-au-Prince’s Quisqueya University and coordinator of post-graduate health sciences programs. “But it’s a good reason to reinforce vigilance and reinforce the measures of prevention … because the rising tendency could possibly invite a second peak.”

So far, those words are falling on deaf ears in the country where public transports, church pews and nightclubs are back to crowded conditions, and Haitians are pouring in for the holidays from abroad.

The reason for the laissez-faire attitude, which still may be rooted in skepticism and stigma, also comes from the fact that Haitians are still only presenting mild symptoms when they get infected. Why is part of the medical and scientific mystery.

“The reason for the lower incidence of detected COVID-19 is not completely clear,” Aldighieri said. “Nevertheless it’s important to point out that the virus continues to circulate in the country. It means that the risk is there; there are cases every day being confirmed by the laboratory in Haiti.”

PAHO, he said, plans to help Haiti with testing by supporting a plan to have nurses visit remote areas, and take samples using 40 testing sites currently located around the country. PAHO also plans to provide rapid antigen test kits as part of an ongoing population-based study to try and figure out what percentage of Haitians may have been exposed to COVID by checking for antibodies from a past infection.

In the meantime, Aldighieri said PAHO “is recommending strengthening surveillance, contact tracing especially in some areas.”

Though there has yet to be a definitive study on why Haitians are not falling ill as rapidly as others and only showing mild symptoms when they do get infected, several theories are being discussed and explored. They range from genetic makeup to age of the population.

Mary A. Clisbee, the director of research for Zanmi Lasante, which runs the University Hospital of Mirebalais, said scientists and doctors regularly discuss the surprise evolution of COVID-19 in Haiti and have tossed around several explanations for the seemingly low infection and mortality rates.

But there is still one nagging question she and others do not know the answer to.

“We really do not have any idea right now of the prevalence of COVID-19 in the country; nor do we know what percentage of the population has had COVID,” Clisbee said.

Like everything else in Haiti, the COVID situation is very complex, said Clisbee, and Zanmi Lasante is conducting social science research investigating how public attitudes about institutional healthcare may be affecting the official statistics.

“You have widespread distrust of the healthcare system, so there are lots of health-seeking behaviors that are based on these kinds of rumors that come from distrust,” she said. “People are concerned if they go to the hospital that they’re going to be given a shot that gives them COVID or if they go to the hospital they will get COVID from the hospital. So people, widely, have not presented to hospitals for treatment for their COVID symptoms, which means they are not tested.”

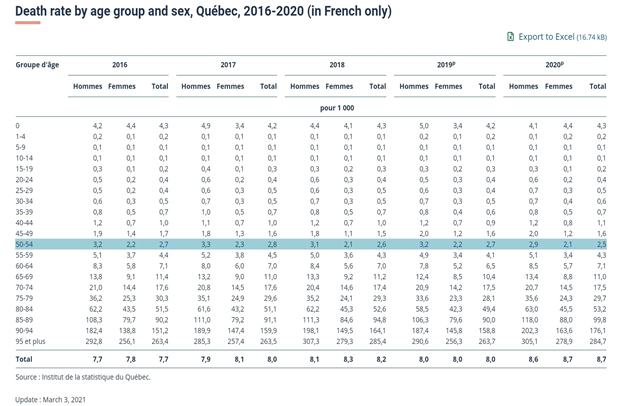

But avoiding doctors doesn’t explain the minuscule death rate. One working theory for that: Haiti has a young population and fewer people with underlying health conditions, which make individuals with COVID-19 much likelier to die.

“More than half of the population is under the age of 24,” said Clisbee, who has a doctoral degree in education. “So the people in that age bracket haven’t been the people who have been dying. They get sick but they don’t get really sick or they are just asymptomatic entirely. That explains a good number of cases in Haiti, we just really have a young population.”

Even anecdotally, the country isn’t seeing the kind of death toll it saw just 10 years ago when cholera hit, and medical professionals were overwhelmed with corpses and deathly ill patients.

“We haven’t had any of that,” Clisbee said. “We do know that even if the prevalence rate is really high in the provinces that the death rate has not been high. That makes you stop to say, ‘Why might that be?’ “

Clisbee, who resides in a rural province in the north, said the official number of COVID-19 infections would lead one to believe that the disease is only spreading in Port-au-Prince. But it is common, she said, to hear people in the rural outskirts say, “Yeah everybody had it up here. Everybody got the flu and they got a fever for a couple of days, but we drank our tea and then we were fine.”

“But they are young. That’s one part of it. The age distribution in Haiti is different,” she said. “Another difference is that in [the U.S.] people who have those diseases, heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, we extend their life by giving them good health treatment. Well in Haiti, people don’t have access to that treatment. … If you’re elderly and you have a disease, you die if you live in the provinces.”

As for the teas and other natural remedies, scientists have found no medical evidence that they work. But there is a strong belief among Haitians in plant-based home brews and that the ones used to fight malaria and reduce fevers are also good for COVID.

Dr. Jean William “Bill” Pape, the co-chair of the presidential COVID-19 response commission, welcomes the continued support of PAHO. Pape said his own GHESKIO health research and training facility in Port-au-Prince has temporarily closed its two COVID-19 units for lack of patients, “but they can be reactivated within a few hours if needed.”

While he remains concerned that Haiti may enter a second wave due to the increased migratory patterns around the holidays, Pape noted it is not the only country, thus far, spared by COVID-19. “Most of the Caribbean and equatorial Africa, many Asian and Middle Eastern countries are in similar situations.”

Several eastern Caribbean countries have successfully kept COVID-19 at bay. But unlike Haiti, their populations are smaller and they have continued to enforce strict COVID-19 restrictions like caps on the number of people who can gather in public, or attend funerals. They also enforce testing and/or 14-day quarantine requirements for travelers, which Haiti does not enforce.

And then there is the matter of wearing masks. After announcing in May that wearing a mask in public was mandatory, the government has since backed off. In fact with no scary spikes in deaths, measures began relaxing in July after the government opted not to extend a national state of emergency and reopened schools, churches and international borders.

The reality on the streets has been large gatherings, no social distancing, and few face coverings.

“This is not our recommendation,” Pape said about the absence of masks. “The government is preaching by example by making the use of masks mandatory in all public institutions.”

Maybe so. But it is also a government of contradictions. While continuing to call on Haitians to practice social distancing, it has allowed businesses and nightclubs to operate without restrictions, while ignoring the advice of its own scientific experts.

Last week, while attending a music festival in the coastal city of Port-de-Paix, President Jovenel Moïse announced that Carnival, which was canceled this year, is back on and will take place in the northwestern Haitian city, Feb. 14-16. Three weeks earlier, his prime minister, addressing journalists at the swearing-in of the new police chief, spoke about not being able to party and reminisced about wanting to attend one of the popular neighborhood block parties in the slums, but being unable to do so, not for fear of COVID-19, but the recent rash in kidnappings.

REKINDLE THE TRUST IN NATURAL IMMUNITY

All these statistics are meant to give the most realist portrayal of the worldwide sanitary situation in a attempt to regulate the dangerous an powerful coranaphobia. For some individual this may nor be sufficient. For these, they will need to rekindle the trust in their God given immune system. We are taking a little stroll into pass pandemics to show that time and time again our great God given immune system stepped up and did the work. Do not forget, in the case of virus, they are mandatory parasite. It will not serve them right to kill the host. They will adapt (mutate, create variants) to become less virulent. This is happening as our immune system become less and less naïve to the bug.

Recalling pass pandemic success

The coronavirus pandemic is far from being the first pandemic encountered in the history of humankind. The world encountered several deadly pandemic and time and time again the immune system stepped to the task. No safety measure, no vaccine, no treatment, no sanitary protocol; … Why is vaccine called to be the ONLY way out of this today? … Namely, an unproven, new technology of vaccine derived from gene therapy.

The main difference is the relentless fearmongering from the media. Could it be that the coronaphobia is more deadly than the virus itself?

Can we rekindle our trust in our God-given natural immunity? To do so we will need to remember its past successes.

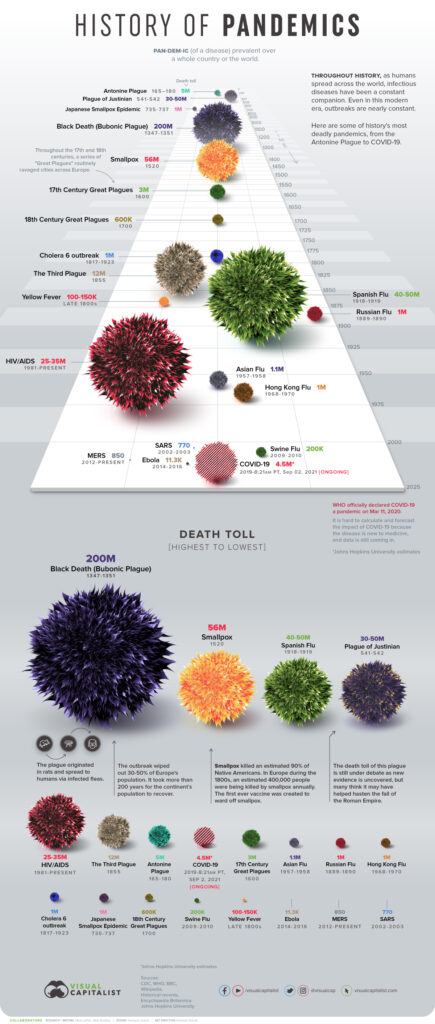

Visualizing the History of Pandemics

Here are some of the major pandemics that have occurred over time:

| Name | Time period | Type / Pre-human host | Death toll |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antonine Plague | 165-180 | Believed to be either smallpox or measles | 5M |

| Japanese smallpox epidemic | 735-737 | Variola major virus | 1M |

| Plague of Justinian | 541-542 | Yersinia pestis bacteria / Rats, fleas | 30-50M |

| Black Death | 1347-1351 | Yersinia pestis bacteria / Rats, fleas | 200M |

| New World Smallpox Outbreak | 1520 – onwards | Variola major virus | 56M |

| Great Plague of London | 1665 | Yersinia pestis bacteria / Rats, fleas | 100,000 |

| Italian plague | 1629-1631 | Yersinia pestis bacteria / Rats, fleas | 1M |

| Cholera Pandemics 1-6 | 1817-1923 | V. cholerae bacteria | 1M+ |

| Third Plague | 1885 | Yersinia pestis bacteria / Rats, fleas | 12M (China and India) |

| Yellow Fever | Late 1800s | Virus / Mosquitoes | 100,000-150,000 (U.S.) |

| Russian Flu | 1889-1890 | Believed to be H2N2 (avian origin) | 1M |

| Spanish Flu | 1918-1919 | H1N1 virus / Pigs | 40-50M |

| Asian Flu | 1957-1958 | H2N2 virus | 1.1M |

| Hong Kong Flu | 1968-1970 | H3N2 virus | 1M |

| HIV/AIDS | 1981-present | Virus / Chimpanzees | 25-35M |

| Swine Flu | 2009-2010 | H1N1 virus / Pigs | 200,000 |

| SARS | 2002-2003 | Coronavirus / Bats, Civets | 770 |

| Ebola | 2014-2016 | Ebolavirus / Wild animals | 11,000 |

| MERS | 2015-Present | Coronavirus / Bats, camels | 850 |

| COVID-19 | 2019-Present | Coronavirus – Unknown (possibly pangolins) | 2.7M (Johns Hopkins University estimate as of March 16, 2021) |

Note: Many of the death toll numbers listed above are best estimates based on available research. Some, such as the Plague of Justinian and Swine Flu, are subject to debate based on new evidence.

Despite the persistence of disease and pandemics throughout history, there’s one consistent trend over time – a gradual reduction in the death rate. Healthcare improvements and understanding the factors that incubate pandemics have been powerful tools in mitigating their impact.

Take note, that in most cases Humanity only relied on their God-given natural immunity . Time and time again it prevailed. It is quite ironic that in this day and age, where we do have life saving therapies, medical advancement, state of the art technology, germaphobia is paroxysmal. One has to wonder why.

Herd immunity to covid 19?

SARS-CoV-2 Infection – Covid-19 Treatment

Your first line of defense is your natural immunity. If it fails, early effective treatments are also available and have been successfully used,

Invermectine

Covid-19 treatment studies for Invermectin

Protocols

Zelenko Protocols: COVID-19 Prophylaxis and Treatment 2021

A Guide to Home-Based COVID Treatment An educational resource from The Association of American Physicians and Surgeons (AAPSonline.org)

An at-home Covid treatment guide from World Council for Health

Management

HOMEWORK

- Using the drugbank database, search these potential therapies against Cov-19:

-Interferon alfa-2b,

-CIGB 258 peptide

-Itolizumab (Dasgupta, 2020; Horta, 2020; Pereda et al., 2020). - Using the graphs from our world in data, drive the cursor on different key date to evaluate the pandemic situation on different key moments.

-The highest of the first wave: April 15, 2020

-The highest of the second wave: August 2nd, 2020

-Beginning of the vaccine rollout

• US: Dec 14, 2020,

• Israel: Dec 19, 2020

• UK: Dec 9, 2020

• India: Jan 16, 2021

• Haiti: July 17, 2020

Looking at the different graphs ask yourself this crucial question for each country; knowing the possible risks of these Cov-vax injections, was mass cov-vaccination necessary at the time of roll-out? Especially for India and Haiti.

Comparing Israel (the most vaccinated country) and Haiti (the least vaccinated country) are those emergency use vaccine candidates effective? Or even necessary? Maybe the drop in cases was the natural course on events following mass infection providing strong reliable natural immunity which could have eventually led to herd immunity. Additionally, we are observing a surge in death rate is Israel, the most Cov-vaccinated country.

Perhaps vaccinating the SARS-CoV-2 vulnerable individual only, would have been the most sensible and responsible way to get a grip on the sanitary crisis. Perhaps the not-CoV-vaxxinated individuals have solid reasons to decline the vaccination when their individual benefit is still questionable.